China’s export growth extends beyond high-tech industries, raising concerns of a potential backlash from countries previously avoiding the trade war. The European Union is expected to impose tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, following similar actions by the US and potential measures by Canada. While few nations share this specific concern due to the lack of their own electric vehicle industries, China’s surplus in manufacturing trade, reaching near-record levels, reveals a broader increase in exports. This surge encompasses various products, including steel and animal feed, which are becoming more difficult to sell domestically due to a slowing economy caused by a real estate downturn.

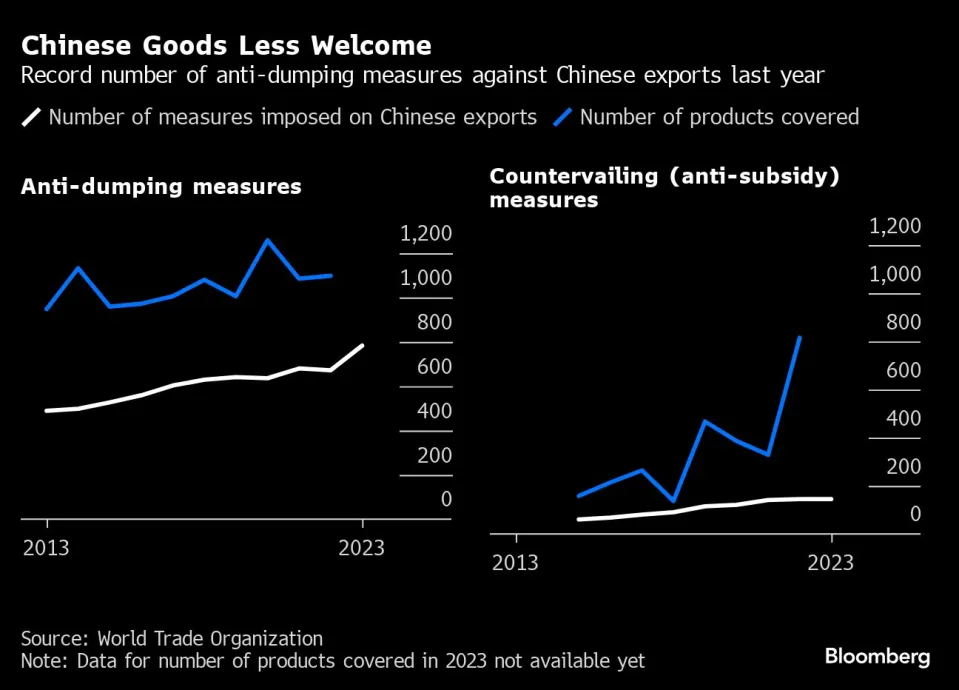

The combination of rising exports and falling prices has raised concerns among countries beyond the US and Europe. China’s trade partners are particularly worried that excess capacity in housing-related sectors may result in the dumping of these materials in foreign markets. This has already led to a backlash, with a significant increase in anti-subsidy and anti-dumping measures against Chinese goods last year. While most of these measures were taken by developed countries in the Group of Seven, other nations such as India and South Korea have also targeted a variety of manufactured goods including steel products, wheel loaders, and wind towers, as reported by the World Trade Organization.

According to analysis of official data by Bloomberg, China’s iron and steel exports reached a record high of 13 million tons in March and remained close to that level in April. This surge in exports can be attributed to the decrease in domestic demand caused by the decline in housing construction. Despite this, local companies are projected to produce one billion tons of steel this year and are likely to increase their efforts to export excess metal, as there are no signs of a housing market recovery.

The continuous decline in prices over the past three years has prompted some Latin American countries to impose tariffs in order to protect their domestic producers and curb the influx of cheap steel. Furthermore, the upcoming increase in US tariffs, scheduled to take effect in August, may redirect even more metal towards Asia.

Already, companies in Vietnam and India are expressing concerns about the influx of cheap metal, which has negatively impacted the profits of leading Indian producer Tata Steel Ltd. Additionally, Thailand and Saudi Arabia are considering implementing new levies to address the situation.

China’s slowing domestic economy is not only impacting the demand and prices of metals, but it is also affecting other industries. For example, China’s exports of soybean meal have increased significantly, reaching almost 600,000 tons in the first four months of 2024. This is nearly five times higher than the previous year. The surplus of soybean meal is a result of reduced demand for pork, leading to fewer pigs. As a result, Chinese processors have been compelled to export their excess supply.

In addition, China has experienced a manufacturing surge in the petrochemical industry. Numerous new plants have been established to produce the essential components for plastic products, ranging from water bottles to football helmets. This boom in petrochemical manufacturing is expected to continue. Researcher Mysteel OilChem predicts that China will bring online enough propane dehydrogenation plants this year to increase its overall capacity by 40%.

The chemical industries in neighboring countries like South Korea and Japan are being disrupted by China’s changing import patterns. China is now importing more raw materials like crude oil and propane, and fewer partially refined petrochemical products. This has resulted in reduced sales for rival plants, leading to the closure of at least one facility in South Korea.

However, there are still many countries that welcome cheaper Chinese goods. South Africa, for example, has benefited from the import of solar panels to help address power shortages. Similarly, India has seen a surge in demand for solar panels, despite its complicated relationship with China, after the Indian government eased a ban last year.

Interestingly, tariffs are not always implemented to keep China out; in some cases, it is the opposite. Brazil and Turkey, for instance, have imposed barriers on direct imports of electric vehicles (EVs), but they have also made efforts to attract Chinese companies to build EV factories in their countries.

A policymaker in Beijing is advocating for further progress in this direction. Huang Yiping, an adviser to the People’s Bank of China, recently suggested that China should implement a version of the Marshall Plan, a US foreign-aid initiative that took place after World War II. His proposal involves China lending money and offering technology to developing nations, enabling them to establish their own renewable energy industries.

However, unresolved tensions continue to pose a threat to global trade, and the situation could worsen if more countries and industries become involved in the competition.

Gita Gopinath, the deputy chief of the International Monetary Fund, warned in a recent speech in Beijing that trade decoupling and the formation of rival blocs could potentially reduce global economic output by up to 7% in the medium term. She emphasized that policies that exacerbate fragmentation are detrimental to the entire world.

This article was written with assistance from Philip J. Heijmans, Dan Murtaugh, and Sarah Chen.